Magnum Nominee Geert van Kesteren just won the Infinity Award for Photojournalim for his book “Baghdad Calling.” From what I hear, the decision is not exactly viewed as uncontroversial… What follows is the take of Stephen Mayes, Director of VII Photo Agency in New York City, both on the book in particular, and on the repercussions of sourcing amateur cell-phone images for photojournalistic purposes in general. JH

Sixteen simple tales of displacement, fear and frustration put a human face on the refugee crisis that has forced four million Iraqis from their homes since the coalition invasion of 2003. Shia, Sunni, Christian and Jewish people, children, parents and partners, workers, professionals and even the son of a senior Saddam General, all are victims of concerted attack and random violence; ordinary lives made extraordinary by unsolicited horrors visited on their houses, since abandoned but not forgotten. And none more powerful than the story that kick-started van Kersteren’s second book on Iraq, the group of doctors forced into exile by the random attack on a colleague, whose brave smile from his hospital bed in Amman, Jordan belied the mortal wounds that took him days after that snapshot was made on a mobile-phone.

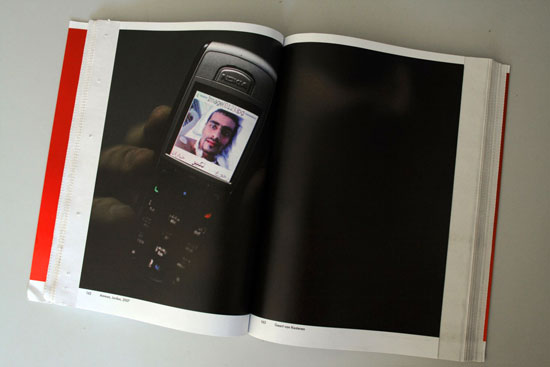

It’s a powerful shot [p.162], intimate and direct, made by a friend holding a phone inches from his face at a time of incredible duress. It’s easy to see how this “found” image inspired photographer van Kesteren to abandon his own camera in favour of the compound eye of a hundred Iraqis recording their lives up-close and personal with mobile-phones, documenting what seems most important to them (the State department records 1.4 million cell-phones in Iraq 2005 swelling to 7.1 million in less than three years). The picture of the dying doctor is very specific to the medium: as a personal snapshot it is intimate, immediate and posed to make a statement that is different from the public pose offered to a professional lens. The smile is for family and friends, intended to reassure and to leave a more benign memory than a raw document of pain and dislocation.

So far so good, but not much further. Van Kesteren took the principle of cell-phone documentary and ran with it, enlisting helpers to trawl the blogosphere and research connections for the wealth of self-generated imagery carried in people’s phones. He found and published 140 phone images, wrapped around the written testimonials with minimal text or explanation and in doing so has debunked the popular theory that the intimacy of the personal phone can somehow substitute for professional observation. It is a popular theory, part of the zeitgeist where the “user generated image” is at the interface of modern technology and culture. But just as giving everyone a car makes many drivers but doesn’t make the roads better nor even improve communications, so cell-phone cameras don’t necessarily enrich our understanding of the world.

Of the three defining characteristics of the mobile-phone image, intimacy, immediacy and ubiquity, ubiquity is proven. So is immediacy – these images are all as close as participants can get to the drama of modern Iraq, but intimacy is a fickle quality. Intimacy is by definition very personal, and as such it’s not necessarily transferable; the author’s intent and the viewer’s understanding are hard to connect even in professional imagery and in the egocentric world of the amateur snap where the image means what the snapper says it means, the significance evaporates with distance. Imposing assumed meaning on these random, often abstract images comes dangerously close to sentimentalism.

These 140 cell-phone images infer intimacy without actually sharing much and this assumed closeness does not substitute for real content. What we see is profoundly uninteresting: it seems that people smile for cameras in Iraq just as they do anywhere else. These images don’t inform, nor stimulate curiosity nor fill gaps left by the powerful spoken testimonials. Fully 40% of the images are general street scenes, which although taken beyond the confines of the Green Zone tell us little about life in modern Iraq. One is reminded of Martin Parr’s Boring Postcard collections that manage to make banal situations look banal, but this is hardly a service when applied in such dramatic and critical circumstances. Some of the images reach an almost delightful level of abstraction that lends them a spurious conceptual aura, such as the pixilated blur that a rare caption identifies as “Videostill mortuary” [p.278] or the inky smudge that we are told is how a town looks by night when the electricity is off [p.256]. I am reminded of Colin Powell’s indistinct satellite “evidence” of WMD and I am also reminded that I shouldn’t fall for the illusion again, even when applied in the seductive context of cell-phone authenticity.

The editors raise the subject of authenticity in the upfront texts, saying that many images were rejected because of “the risk of digital editing” and “suspect provenance or propagandistic nature”, thereby bleaching some of the most interesting aspects of the cell-phone genre. If we’re going to truly embrace this vernacular medium we shouldn’t pretend that it substitutes for professional journalism but instead take it for what it is: an expression of what people want to say using whatever tools they can bring to bear.

The unfortunate design exacerbates this dismal representation. The decision to print the amateur images on newsprint is presumably intended to convey the immediacy and veracity of up-close news imagery but actually creates a sense of disposability. The designer has chosen to run each image full-frame across double pages creating two problems: enlarging a picture intended to be seen at three square inches to over a hundred square inches does little to enhance the image, and it also reminds us of the amateur tendency to place the subject in the centre of the frame resulting in the book’s hungry gutter eating many of the key elements.

The end result is interesting as another modern typology demonstrating those subjects that people find most interesting to photograph: street scenes (often from within traveling cars), burned-out cars and celebrations. But what does this tell us about the plight of four million displaced Iraqis? It is a brave experiment and should be respected as that, but it is also reminder of the emperor’s new clothes. Many of us are mesmerized by the cultural presence of the cell-phone and we are hoping to invest value in this new tool of communication, but this theoretical wonder is not yet borne out in its practical application.

Baghdad Calling, Geert van Kesteren, Episode Publishers, 2008.