“Dear Dr. Hare,

this year, it seems that I just can’t bring myself to go to Europe for the summer. I don’t know what it is. Maybe the new apartment? I feel like I live the life of some pampered movie star here, compared to the old place up in the sky near Hudson River, with the wind howling and all. When a light bulb goes out, one mouse click on the building homepage, or a quick call, and a friendly person shows up and puts in a new bulb. We found a company that is now fixing our old furniture – pieces that broke down over the years, while moving from place to place, and I can’t help to see something symbolic in that. I look at the park, walk around the new place, still somewhat in disbelief about my new life, and wonder if the old saying is true after all – that once you cross a bridge to Manhattan, you never have to cross a bridge again.

Which is not entirely true for me: I have quite a few trips lined up across the continental US – the West Coast again (whatever people say, I loved it), Miami (which I also kind of like), and other places. Compared to flying to Europe, flying across the US feels to me like taking a cab. And, as you know, while I love to work hard, I also tremendously value convenience. But I do worry: Am I getting old and mellow?

And where does this leave my Mountain friends? I will be back in the Dolomites next winter, but for this summer, I just can’t bring myself to book a flight. Or, I know that I most likely will go in the end, but it puzzles me that I am even hesitating. Last night we watched the latest Bond movie (via Netflix – as you know, I do not go to movie theaters), and I found funny that each episode gravitates back to the same old sets. So far, I’ve not been like that – I have not been to the town where I was raised for many, many years, and I may never go back at all. I’m just not interested.

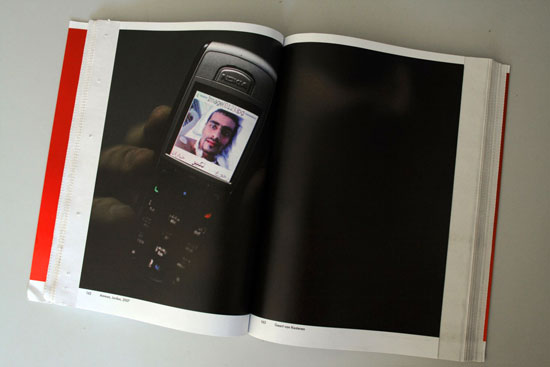

OK, I’m rambling. Not much new here. I had strawberries today and made a photo of them, on a new desk I just bought. I feel very well, don’t worry (with a lot of exercise and the warmer temperatures, the arm feels much better now and it may heal almost completely). You seemed so rooted and content in your office when I last saw you there, I wonder whether I feel the need to entertain a life away from my computer-plus-camera at all.

Jens”

“Dear Jens,

I look at the photo, and I think, isn’t that the table from the Swiss design company you mentioned? So, you are eating your Manhattan strawberries on your Swiss (if not to say mountainy) table, and tell me that you are losing your grip on your connections to Europe. What can I say? I think they are much deeper than it may feel to you now, and I think they are very valuable. Do go back, and do find a place in your life for friendship and for the past.

Of course, for the sake of our conversations, I may wish that you stayed, and for once kept a regular schedule with your sessions here. But I am not sure that this is what I should be saying. The fact that you are writing to me about this tells me that inside of you you know that your friends in the mountains will feel cheated. Do not they worry about your arm? Will they not feel your staying away as punishment and retreat? I think you should go, and make people see that you are still their friend.

But here is another consideration: If you feel that you need time to heal from the shock of the accident, then they shall have to understand. Only don’t make it seem like you are pulling back. Not everyone takes solitude as well as you do, and you know, I am not even sure that you take it as well as you think you do.

You are right to enjoy your new apartment, after the wear and tear of the last years, which, I know, affected not just your furniture. But never forget the old over the new. I can’t give you reasons for this little piece of advice, but it is dear to my heart.

Let’s speak soon in person,

Dr. Hare”